Someone to Admire

In my family, there is a habit of watching old VHS tapes together every few years. This isn’t planned, but whenever it happens, my stomach sinks, despite how happy my sister and cousins are to see our childhood selves reanimated. Recently, I realised that I don’t enjoy this process because I don’t know who I am now represented in the child on screen, and I haven’t for quite some time. Of course, we all grow up and change so much that our childhood selves almost feel like theoretical shadow lives, rather than real memories. But usually, there is some hangover from our past that has leaked, despite all odds, into our adult years. A tendency for roguery, a tenacity of spirit, perhaps. I don’t see anything of myself in the little girl with freckles on the grainy screen. She was a girl who was called a force, a powerhouse. She was a girl with strong legs for swimming and the ability to land a punch with unprecedented force. She was healthy.

No matter how much time passes between then and now, I will never forget how I felt in that child’s body. That’s why I know it was real; the only way I feel connected to the girl is through her energy. My body felt both stocky and tall, both fragile as fine bone china and strong enough to pull oxen. The deciding factor in how physically strong I felt on any given day was always whose eyes I looked through. If adults called me small or remarked that I had a lot of growing yet to do, I would look at my knock knees and scowl. But when I felt the wind in my lungs as I ran a relay race, I knew that deep down, I was invincible. Even though I’ve since learned, somewhat brutally, that that isn’t true, I know that it is the feeling, the echo of that invincibility, that has kept me upright all these years.

My chronic illness journey began a month after my eighteenth birthday with a bacterial infection that knocked me on my ass. It’s been twelve years since then, and I have never been the same, but somehow, there are those in my life who still expect to see the child who proved to be a surprisingly good shot putter. The girl who was cheeky and fiery because she had the energy to be! Friends from primary school, my grandparents, even. To them, I will always be playing a part, breathing false life into an echo of myself that I cannot even remember if it is accurate. I don’t try to let down the façade with them. I might have, once upon a time, but then I realised one crucial fact – no one likes a tired girl as much as they do a fiery one. Tired girl is soulless and limp. She’s no fun. After a while, you start to even bore yourself.

The what-ifs carry their own pain. They’re worse when they aren’t even your own what-ifs. It’s the musings of your mother, who cannot help but say aloud that she wonders who you might have become if your health hadn’t held you back. Can you imagine? She asks, eyes gleaming. And you smile because, of course, you can imagine. You’ve been imagining for so long that you know you will never stop imagining. Imagining a life when a tired girl was temporary, and the pain faded with a single paracetamol, like all the doctors claimed. Some what-ifs are not said, but pack a powerful punch. The what-ifs that come on the big days that are supposed to be significant milestones that you might never have achieved because of your failing health. Graduations, new jobs, and passing driving tests. Those moments in the sun are always tinged with a chill that you have only achieved despite something. You will never simply achieve. Or live, without the context of illness. People won’t say it when you’re standing on top of the altar in a white dress or tossing your cap in the air, but they will be thinking it. God, isn’t she great? And after all she’s been through?

People do talk about the grief that comes with developing a chronic illness. They talk about how you’ll mourn the life you never got to live and be angry for a while. It’s always for a while, though. They don’t tell you that you’ll never stop grieving. That you can’t, not so long as the rest of the world keeps living and dancing and breathing fully and getting full nights of sleep and feeling refreshed. Over time, this grief changes form. It warps and turns ugly, forming barbs of resentment. You start to grow a new kind of weary. The type that lashes out whenever your friends roll their eyes at you having yet another early night. The kind that starts to imagine your friends rolling their eyes in the first place because, if they were the type to judge, you wouldn’t have become friends with them in the first place.

I also cope with this grief in an unhealthier way still, I think. I’ve coped by trying to be what I most dislike, what feels most disingenuous – someone to admire. I feel shame in admitting that I want to be admired, but not enough to not acknowledge the truth. I want my achievements – my writing, my academics, my professional achievements, my kindnesses – to be seen because otherwise, without the acknowledgement, the cost I paid to achieve them might not have been worth it. The cost comes in many forms beyond simple fatigue. There is the external cost, visible to all, no matter how much you hide it. Someone is going to see the tears your university degree cost you and notice the dark circles under your eyes. Your family might eventually do up a mental tally and realise you haven’t seen your friends in a while. Still, it’s all good because you’re going to graduate with a 1:1. The external cost is significant, but there is an ugliness no one sees. For me, doing well in life, whatever that even means, despite my health, means I begin to expect excellence at every turn. This web stretches far beyond me, and I start to think: if I am willing to pay the cost, if I am willing to hurt to achieve, why aren’t you, you who does not hurt as I do? There is a particular vicious edge to these thoughts that, over time, revealed itself to be precisely what it always was – resentment. Resentment of others, yes, but mostly of myself.

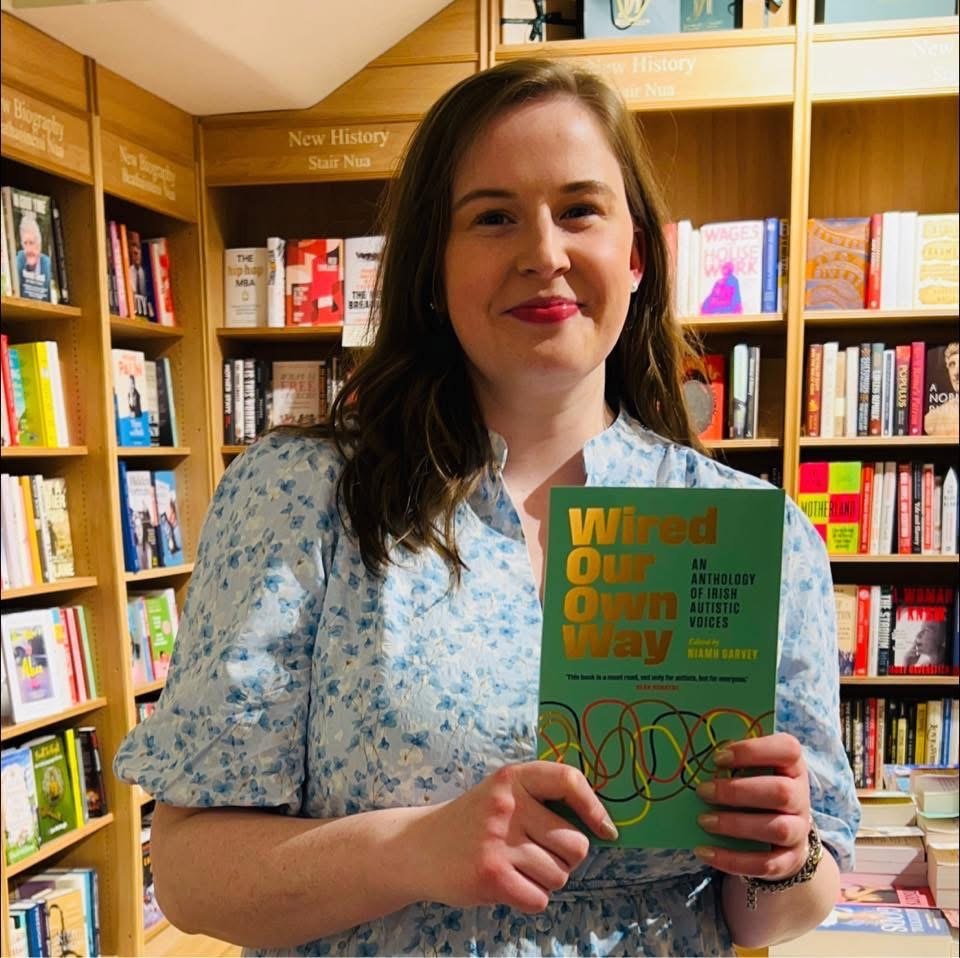

I work in disability services. My PhD topic is related to disability studies. I write fiction about disabled people. My Instagram page regularly refers to my own disabling experiences. This bloody post is all about such experiences. And yet, something ugly crawls out from just under the surface of my skin frequently, growing caustic toward others who suffer as I do, who experience the world as I do. Recently, I saw an autistic woman, probably close enough in age to me, being so blatantly autistic that I felt a rage so raw and searing within my chest for a mere second that it scared me. You see, this woman was advocating, publicly, for her needs to be met and was communicating in a manner that helped her communication needs and whilst wearing an outfit that was entirely geared around characters from a show she loves, essentially cosplaying in her everyday life. And do you want to know her greatest crime? She looked happy. She looked at ease with herself, all while being herself. I sat near her, wearing a shirt that made me want to peel off my skin because the collar was too high, and mascara that I felt every lumpy ounce of flicking my eyelid all day. I sat near her, trying with utter desperation to become like everyone else, and no one even asked me to do it. And here this woman was, an unbridled example of self-acceptance, and the world kept moving.

My feelings in these moments are lightning quick and bring me no shortage of shame. First, I feel a fury so fierce that it might have been fueled by the heat coming from the Earth’s core. Each time it hits, I am staggered by its force. Then, almost immediately, guilt consumes me for directing such anger toward someone entirely undeserving. Especially when I know that the anger lies with me. I feel angry that I have spent so much time trying to be other than I am when others do not abide by such silly self-made and self-limiting rules and thrive. Mostly though, more than the anger, I feel afraid that I do not know how to stop trying to cut corners off myself, to stop trimming the edges of my personality un’s left is so flimsy it barely stands up. I do not know how to ‘unmask’ and to be a me that is not prioritising the palatability of my being for others. I do not know how to be honest about my chronic illness and to curb this need to achieve. I do not know how to honour my neurodivergent self in all, or any, settings.

I think that is why I do not like seeing my younger self on the VHS tapes. She didn’t know how to stop pleasing others either, but she did know, at least when she was alone, how to please herself. My grip on my wants grows slacker each year, and I wonder, with no shortage of fear, if I will continue to fade away. From oil paint to watercolour, my very self will grow more porous, more susceptible to the most meagre rain cloud. I'm unsure how to solve this, but I do know that acknowledging it is the first step. At the very least, I'm sure that I was born to be honest. And so, honesty will become my north star. I will have to hope that as long as I am reaching for honesty, I am reaching for myself.

Until next time,

Jen x